Blogging the past few days about Robert E. Howard & David Gemmell has gotten the old sword & sorcery juices flowing, so I thought I’d post about another one of Robert E. Howard’s S&S creations, Kull of Atlantis. There are a lot of links between Kull and Howard’s more famous creation of Conan. Both of them made their original appearances in Weird Tales; Like Conan, Kull has subsequently appeared in a number of other mediums, such as movies, comics, B&W illustrated magazines, and figurines; and both of them are also barbarians with adventurous backgrounds. In Kull’s case, he was a slave, pirate, outlaw, and gladiator before he followed the path of Conan and became the general of the most powerful nation in the world (in Kull’s timeline this would be Valusia). And like Conan, Kull eventually led the revolution that allowed him to ascend to the throne. But without question, the most important connection between these two characters is that without Kull of Atlantis there never would’ve been the icon known as Conan the Barbarian.

The character of Kull preceded Conan in print by slightly over three years. Kull first appeared in the August 1929 issue of Weird Tales, in the story “The Shadow Kingdom.” There would only be one other Kull story published in Howard’s lifetime, “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune,” which appeared in the September 1929 issue of the same magazine. Kull did appear in another story before Howard committed suicide, called “Kings of the Night,” but this story is actually about another of Howard’s primitive heroes, Bran Mak Morn, the last Pictish king—Kull’s role is secondary in this crossover tale. There was also a poem about Kull called “The King and the Oak” that Weird Tales published about 3 years after Howard committed suicide. Other than these 4 pieces, none of Howard’s works involving Kull would be published until many years after his death.

Strangely enough, a very strong argument can be made that the most important story Howard ever wrote involving Kull doesn’t involve any of the aforementioned works. Instead, it might be “By This Axe I Rule!” In this story, Kull is new to the throne of Valusia, the most powerful nation in the world, before it became rocked by the Cataclysm that led to the birth of Conan’s Hyborian Age. A group of noblemen, jealous of Kull’s position and despising his barbaric background, conspire to assassinate him while he sleeps in his chambers. Instead, they stumble upon a fully awake king who is armed to the teeth. As you might expect, battle ensues. Farnsworth Wright, the rather brilliant editor at Weird Tales, went on to reject Howard’s tale.

At some point down the road, Howard came up with the idea for Conan. He wrote a pseudo-history of Conan’s world in his essay called “The Hyborian Age,” providing the necessary backdrop to write in Conan’s world, and then settled in to write his first tale of the iconic Cimmerian. That first story was “The Phoenix on the Sword.” “The Phoenix on the Sword” is an in-depth rewrite of “By This Axe I Rule!” The basic plot I outlined above is the same. Besides altering the world to take place in Aquilonia instead Valusia, Howard also added several subplots and a magical element absent in the original story. Howard would go on to sell this tale to Wright and the rest is history.

Howard would never sell another Kull tale after he started selling his Conan tales. You might think this was because with all the similarities between Conan and Kull, it made little sense to continue writing about Kull when Conan was more successful. I don’t think this is the case. Despite all their similarities, Conan and Kull are very different characters. In my post about Conan, I mentioned that Conan is not a philosopher or a man of deep thoughts. Kull very much is. Kull of Atlantis cared about the nature of life and existence. Despite his barbaric background, Kull didn’t need to conform to civilization nearly as much as Conan had to. His thoughts and beliefs were far ahead of his time—but, like Conan, when necessity demanded it he was more than able to shed the frills of the civilized world. It’s this philosophical bent of Kull’s that makes him a worthy addition to the literature of sword & sorcery.

As an example of their differences, you need look no further than “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune,” which happens to be my favorite Kull story. Kull, grown restless with the ordinariness of life, learns of the wizard Tuzun Thune and seeks the wizard in search of wonders and a greater understanding about the nature of the world. When he gazes into the Mirrors of Tuzun Thune, he gets far more than he bargained for. Although Howard notes that Conan was prone to bouts of melancholy, Conan would never seek arcane wisdom to brighten his mood. Instead, he would tie one on by drinking prodigious amounts of whatever was available, crack a few heads if anyone decided to start something, and ultimately polish off the evening with a lively wench (or several). Simple cures for a simple man. And if he came anywhere near the Mirrors of Tuzun Thune, his first reaction at beholding such black sorcery would most likely be to shatter the glass with his sword.

But Conan’s cures for the blues are among the things that have made Kull restless. Kull seeks something more, something other. He seeks answers. Conan found his answers long ago. To Kull, Conan’s most basic primal fears represent exotic wonders that demand further investigation. The rise of these two barbarians may have followed similar paths, but the men wearing the crowns are two very different individuals.

It is with good reason that many of Howard’s stories about Kull failed to be published during his lifetime. Most of his rejected tales about the mighty Atlantean were written by an author still learning his craft. The battles and ideas often lack the primal and evocative beauty found in Howard’s later works, his world-building wasn’t as detailed, his authorial voice and style were still developing, and while plotting was never Howard’s cup of tea, the plots found in many of his early Kull works are not up to snuff. But there is a fascination with the writings of Howard, especially his supernatural tales. This fascination has bred a curious hunger that leaves his fans more than willing to read his unpublished works (myself being no exception). And so, many of the stories better left relegated to the proverbial drawer have found their way into print. Yet if you’re a true fan of Howard, reading such tales is a worthwhile experience. Every so often you come across that spark of primal genius that would lead to him penning some of the greatest sword & sorcery tales of all time. Tracing the evolution of his writing is absolutely fascinating, and many of his Kull stories offer a window into the writer that Howard would become.

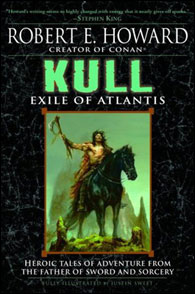

If you’re curious about Kull, Del Rey has released a comprehensive volume of the Kull tales called Kull: Exile of Atlantis. This book is part of the same series that collects all of Robert E. Howard’s Conan tales, as is, put together quite nicely. And while I may sound dismissive of some of Howard’s rejected Kull works, I emphasize what I said earlier: Kull is a worthy addition to the literature of sword & sorcery, if for no other reason than the fact that as the thinking man’s barbarian, he is the exact opposite of the stereotype that is so common to this sub-genre. Fans of S&S who’ve yet to familiarize themselves with Conan’s predecessor should rectify this gap in their reading at their earliest convenience. Considering how few stories about Kull were published during Howard’s lifetime, the Atlantean’s contributions to S&S are quite significant.